Religion

When one thinks about religion he might ask himself why he believes what he does and how he came upon such beliefs. In most cases the question "how" can be answered by examining one's early childhood. No doubt each person was born into a family, community or nation with a shared religious belief. In my own case I was born into a Roman Catholic family in a largely Roman Catholic south Louisiana, in a largely Anglo-Protestant and Roman Catholic United States. I had few questions about my faith in those early years except for those I was taught to ask. There are two I remember to this day, "Who made me? --God made me," and "Why did he make me? --Because he loves me." The questions seemed simple, as well as the answers, and to a child they made perfect sense. I remember feeling a sense of pride that I could answer these questions so deftly.

In later years of childhood I began to ask my own questions. After sitting through countless hours of Sunday sermons I would ask myself, "Am I doing what I am supposed to be doing, that which is right by God?" This led me in my teen years to decide to enter the seminary. I had a clear awareness of the notion that God was a god of love. He loved all of his human creation. He was fatherly, to whom we could address in silent prayer as "Father." There was also Jesus his son, who was even more accessible than the Father, to whom we could speak to as a brother or our closest friend.

I believed that there was one great commandment, "to do unto others as you would do (or have them do) unto you." This was supposed to be the second of two commandments, but the first never made much sense to me. "Love God with all your heart, all your strength, all your soul, etc." Why all the hyperbole? What in fact was "all you heart, all your strength, etc?" In later years I came to have a problem with the superlatives as well. God is all this and all that, ever this and ever that. Why wasn't it enough just to love other people. This was tangible. If one succeeded at this, shouldn't God be happy enough with him? St. Peter's Basilica (Feb. 2004)

St. Peter's Basilica (Feb. 2004)

I went on to join the seminary. I imagined myself at some point in the future being a priest in an overseas mission, looking after the needs of the downtrodden. But the ceremonial aspects of priesthood began to seem bogus. I couldn't see how such things had any relevance in the total scheme of things. The priest wore his garb, would say the "magical" words changing wine into blood, raise his arms in this or that fashion. As uninspiring as the ritual seemed, it was supposed to be more than mere symbolism. It was supposed to be in some fashion a manifestation of God's presence and power. What, I thought, did all this have to do with helping people in need? I could do that without wearing robes or raising my arms in some holy fashion.

In time it seemed clear to me that people did things within religion not because it was ever made plain that it was logical to do so, but simply because they were led to believe that they were supposed to do such things. As a university student in Hawaii I began to gain a more reasoned perspective on faith. This was through Christianity preached from the fundamentalist perspective. Tradition and ritual were scorned in favor of a reasoned analysis of what the words of the Bible proclaimed. I liked this "reasoned" approach. Religiosity came to seem more based on what one could understand and explain.

Time and circumstances, however, would lead me to begin asking questions again. A critical question became the authenticity of the Bible upon which one's total faith was to be based. Despite spurious arguments to validate the sanctity of the sacred text, it just seemed wanting in so many ways. It was incoherent, sometimes contradictory, vague in places, seemingly incomplete, certainly not modern and very culturally biased. Finally, at the center of Christian faith was the belief that Jesus was not only a historical figure but present eternally in the spirit. For the believer his kingdom was now and he was among us. Of course you couldn't see him, but you could feel his presence. It would manifest itself through other people, events and circumstances in our lives.

It all made sense and in deed I felt it, until I found myself separated from the fellow believers who had become my closest friends. If all of that was Jesus then how come it was no longer present when I was no longer in the presence of my Christian friends? "Wake up!" I thought. What's God got to do with any of that? All that I had felt was Jesus, was merely the friendship and warmth of other humans. Put this together with the absolute and final "word of God" being written and bound in such a mediocre fashion and I was finally ready to accept that religion and God were creations of man.

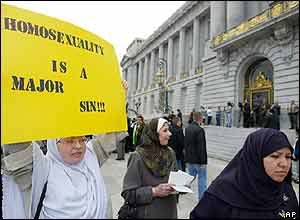

That didn't mean it was bad but it certainly wasn't what it claimed to be. It clearly served a useful purpose in many people's lives and perhaps for humanity at large. At the same time it was responsible for many great acts of hatred and cruelty throughout the past and present.

Now, and for some time, having been freed from the shackles of religion, I wonder what it is that I can do for myself and for others--now that I have become "enlightened." Perhaps one can say that all I have done, if for no one but myself, is discredit Christianity. What, then about other faiths? My answer is that they are all quite similar on a fundamental level. They seek to explain reality and dictate human behavior on the basis of an invisible and omniscient authority. They all require the believer to base his actions not on what can be shown to exist but that which through faith ought to be accepted. People are quite simply born into a religion just as they are born into the citizenship of a country. They are no more likely to abandon their religion as they are to abandon their nationality. St. Peter's Cathedral (Feb. 2004)

St. Peter's Cathedral (Feb. 2004)

In the final analysis, perhaps, a distinction should be made between religion and faith. Faith is a testament to what one believes to be real and true. Religion is perhaps simply an element of one's cultural identity. In that sense I am a Christian and always will be. I hold to the values of Judea-Christianity while I profess no creed. I stand in awe at the magnificent monuments and works of art created over the centuries in the name of Christianity. I will always see the cross as a beautiful and elegant symbol. I watched Mel Gibson's "The Passion," and was moved by the movie's artistry and the beauty of its central characters, Jesus and Mary. Nevermind that I believe Jesus to have been no more than a man, and any historical accounts of what he said or did to be open to question. In the final analysis perhaps I am no less Christian than I am an American. It's simply what I was born into.